LOL: How Washington Keeps Making Healthcare Worse

If only we could afford to laugh; but it’s not funny.

This was a tough year for everyone. Premiums went up, deductibles climbed, and employers found themselves paying more while their employees received less. Unfortunately, the warnings for 2026 don’t look any better. Total health benefit costs are expected to rise by 6.7%, pushing the average per-employee spend above $18,500, which is well ahead of wage growth and inflation. Meanwhile, somewhere in Washington, politicians will promise solutions. We all know they won’t deliver, because they can’t. More on that later.

First, a quick confession: When three-letter abbreviations started to dominate text messages nearly two decades ago, I was a little slow on the uptake. For years, I thought LOL meant “lots of luck,” and that’s how I used it. It wasn’t until a bewildered friend replied “HUH?” that I learned everyone else used LOL to mean “Laugh out loud.”

It was a small misunderstanding, but it stuck with me. Sometimes the best intentions meet a system, or a culture, that doesn’t work the way you expect. Case in point, American healthcare. A system this massive, this expensive, and this disconnected from the people it’s supposed to serve can leave you shaking your head, or sometimes wanting to LOL, because the only reaction left is to laugh.

However, to the politicians who keep promising they’ll “fix” American healthcare, I still say, “Lots of luck.”

The rest of this article comes with another LOL: “Lots of love.” Because I truly hope it opens eyes. We will never make any progress until we acknowledge the true drivers of our healthcare costs. Right now, I don’t hear anyone talking about the real problems.

Out of love for every American, I pray that everyone embraces the need for greater understanding.

The bill that keeps growing

That $18,500 figure isn’t an anomaly. It’s the fourth straight year of increases above 5%, following a decade when costs grew around 3% annually. In 2025, premiums rose faster than employees’ wages, forcing employers to raise deductibles, hike copays, and shift more costs onto workers who can least afford it. Next year won’t be any easier. Employees’ share of coverage costs typically rises at the same rate as total costs, meaning affordability will be an even bigger challenge.

Employers are already doing everything they can, building narrower networks, adding plan options, and following their brokers’ advice. It’s not enough.

Policymakers in Washington will continue promising relief—another bill, another reform, another administrative “fix” that will finally bend the cost curve.

They’re lying to you. Not maliciously, perhaps, but lying nonetheless. As uncomfortable as it may be to acknowledge, the truth is our government cannot engineer a better healthcare system. It has never been capable of doing so, and every time it tries, your costs go up.

The unvarnished history of modern American healthcare

If you want to understand why healthcare costs keep rising, you have to look outside of healthcare. The system you’re paying for today didn’t start in a hospital; it started with our military.

In the early 1900s, the U.S. Department of War (renamed the Department of Defense, and now back to the Department of War at an estimated branding cost of $2 billion) formalized the use of cost-plus contracts, the practice of reimbursing contractors for all approved costs, plus an additional profit.

They were widely adopted during World War I and World War II to encourage businesses to produce war materials quickly without worrying about the unpredictable costs of materials and labor during wartime. Then, throughout the Cold War, cost-plus contracts were used to build military capacity at any cost. Regrettably, they delivered more than might; they delivered waste in the form of billion-dollar overruns and $640 toilet seats because there was no incentive to control costs. The more they spent, the more they earned.

In his famous farewell address, President Eisenhower warned us about the military-industrial complex, cautioning that it would breed inefficiency, runaway spending, a lack of market discipline, and corruption.

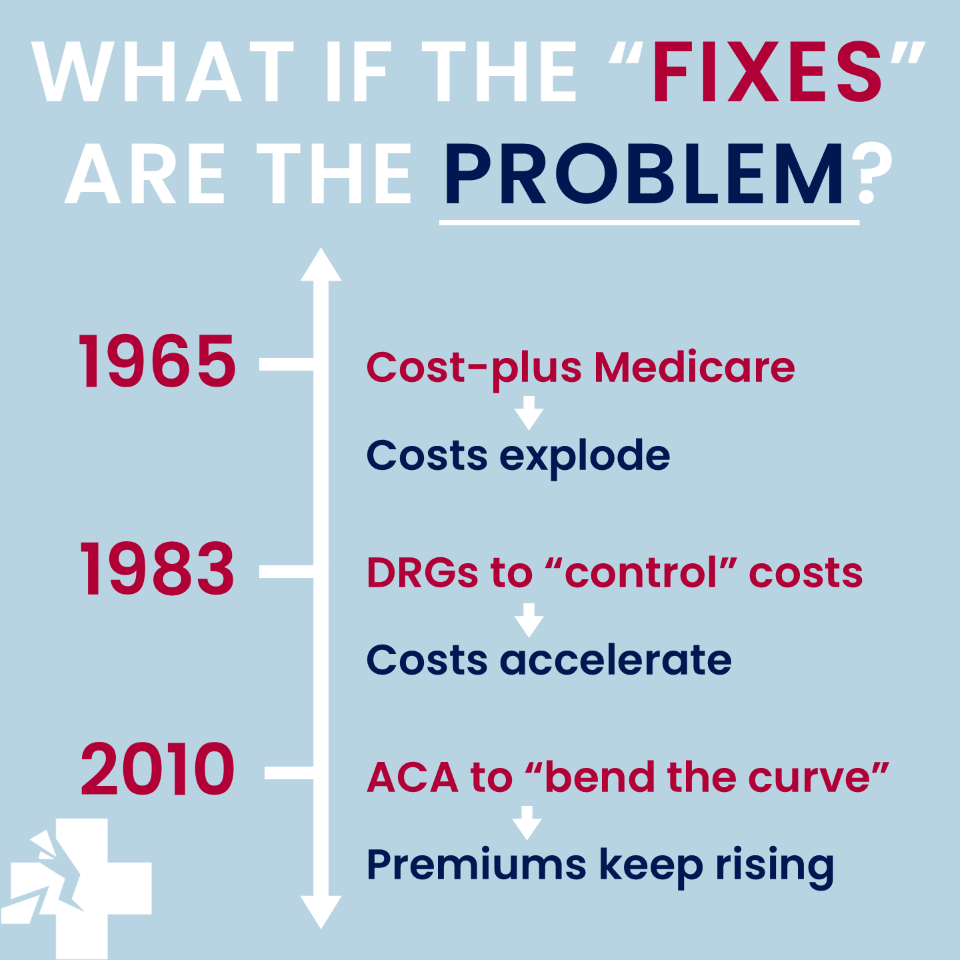

Then, in 1965, Congress made the same mistake with healthcare.

When Medicare launched, it adopted cost-based reimbursement. Hospitals were paid for all “reasonable costs” plus a margin, just like defense contractors. There was no penalty for spending more, no connection to value, or pressure to be efficient.

Costs exploded.

Just as the defense industry led all other nations with unmatched spending, Americans soon found themselves leading the world in healthcare expenditures. The same public that once took pride in military investment came to disdain the spiraling costs of healthcare. The paradox stems not from the nature of the service, defense versus health, but from the persistence of a reimbursement method that rewards volume rather than efficiency or value.

The defense industry eventually learned. Slowly and grudgingly, it has moved in recent years toward competitive procurement. Healthcare has yet to learn its lesson. The cost-plus mindset remains embedded in every payment system, every regulation, and every reform. And why not? The result is very lucrative.

The 1983 “fix” that created the billing industrial complex

By 1983, Medicare spending was spiraling out of control. Congress panicked. They needed to rein in costs. Instead, they responded by doubling down on intervention. The Prospective Payment System (PPS) and Diagnosis-Related Groups (DRGs) were introduced, which paid hospitals a fixed, predetermined amount for each case regardless of actual costs.

In theory, this should have worked. Hospitals would have an incentive to provide care efficiently, since they’d keep the difference between the fixed payment and their actual costs. But hospitals are businesses, and we all know businesses don’t accept lower revenues. They find ways to adapt. Although it was unintended, in hindsight, what followed was entirely predictable:

Upcoding became an industry.

If Medicare paid more for a complex case than a simple one, hospitals documented more complexity. Medical coding systems, once a simple tool for categorizing diseases, became the central financial instrument of healthcare. Entire departments were built around maximizing “case-mix index” and documenting the most severe diagnosis that could be justified.Care shifted to less regulated outpatient settings.

Until recently, DRGs only covered inpatient care, so hospitals moved procedures to outpatient facilities, ambulatory surgery centers, and other venues where they obtain more generous reimbursements.Consolidation accelerated.

Larger hospital systems could hire more coders, negotiate better rates with commercial insurers, and achieve economies of scale in gaming the payment formulas. Regional health systems merged into near-monopolies. As a result, competition decreased and healthcare prices went up.Administrative costs skyrocketed.

The complexity required to navigate DRG payments, document for maximum reimbursement, and manage multiple payment models required armies of administrators. Healthcare’s administrative burden is now a material driver of spending.

Rather than driving costs down, the government-imposed payment system industrialized revenue optimization. Sadly, patient care was no longer the central goal. Navigating a complex web of codes and rules to protect financial margins became the administrative focus.

Every one of these adaptations was a rational business behavior. That said, I don’t believe the system was broken by market forces. Healthcare was broken by payment models that were designed by people who didn’t understand markets. These models were then embraced by those who understood all too well.

States added accelerants to the fire with anti-competitive regulations

While Medicare was creating perverse incentives, states were busy erecting barriers to competition. Certificate-of-Need (CON) laws were passed in most states, ostensibly to prevent “overbuilding” of healthcare facilities. The theory was that too many hospitals would lead to wasteful duplication and higher costs.

The reality was the opposite. CON laws require anyone wanting to open or expand a healthcare facility to first obtain government permission. They must prove that the community “needs” the facility. Existing hospitals get to weigh in, essentially giving incumbents veto power over potential competitors.

This is not how markets work. In a functioning market, if an incumbent is overcharging or underperforming, a competitor enters and takes market share. The threat of competition disciplines prices and improves quality.

CON laws eliminate that threat. They protect established hospitals from new entrants. They ensure that regional monopolies can maintain high prices without fear of being undercut.

Far from controlling costs, these laws fostered the very market consolidation that drives prices higher today.

You’re paying those monopoly prices right now.

The ACA doubled down on a broken system

Fast forward to 2010. Healthcare costs are still rising and millions lack insurance. Washington promised a comprehensive solution that we’ve all come to know as the Affordable Care Act (ACA).

The ACA succeeded in expanding coverage. That’s worth acknowledging, but expanding coverage inside a dysfunctional economic model doesn’t make that model work. The ACA treated a symptom, lack of insurance, while leaving the underlying disease untouched: distorted pricing, consolidated market power, disconnects between supply and demand signals, and decades of misaligned incentives.

You likely noticed your premiums didn’t go down after the ACA. They went up. Your employees’ deductibles and out-of-pocket expenses didn’t shrink, they grew. Now, for those eager to blame the ACA and call for its repeal: don’t misread this as a political critique. The ACA is a minor player in a sixty-year story of structural failure. It didn’t create the broken system. It tried to expand access within it. That was a fool’s errand.

Repealing the ACA without confronting the foundational problems would simply unleash chaos. You’d expose millions to the constraints of the same broken system the ACA, however imperfectly, tried to address. The DRG-based administrative pricing would still be there, the revenue-optimization incentives would still be there, and the anti-competitive barriers would still be there.

The problem isn’t that the ACA didn’t go far enough. The problem is that it marched further in the wrong direction toward more complexity, more administrative control, and more government engineering of a system that cannot be centrally planned.

So where does that leave us?

The current trajectory is not sustainable. Healthcare now consumes 17.6% of GDP. By 2033, it will reach 20.3% ($8.6 trillion). One-fifth of everything we produce will go to healthcare.

This means your costs will continue rising faster than your revenues, your employees will shoulder more of the cost, and your ability to invest in wages, technology, and growth will continue shrinking.

If we haven’t already, we are reaching a tipping point. Something is going to break. Either employers will stop offering coverage, triggering a crisis, or the government will impose price controls, triggering shortages and rationing.

What would fix this?

Each layer of bureaucratic engineering, from payment systems to price controls, has failed. This is because a system as dynamic as healthcare cannot be centrally planned. Every administrative “fix” creates new loopholes and prompts compensatory behaviors that lead to more complexity and cost, requiring yet another layer of regulation.

It is a fallacy to believe we can engineer our way to affordable healthcare. Greed is a human constant, present in any economic system. The function of a true market is to harness self-interest through competition, forcing providers to compete on price and quality to win customers. Our current system does the opposite; it rewards navigating bureaucracy.

If we are serious about fixing healthcare, we must start trying to liberate it. A genuine market-based solution would require bold, fundamental changes:

Radical price transparency: Prices for services must be simple, clear, and available upfront, allowing patients to shop for care just as they do for any other good or service. Not buried in chargemasters. Not negotiated in secret. Transparent.

Elimination of anti-competitive barriers: Repealing CON laws and other regulations that limit the entry of new, innovative providers would unleash competitive pressure on established players. We need to let competitors enter and let the market work.

Consumer-directed financing: Empowering patients with tools like Health Savings Accounts (HSAs) combined with catastrophic coverage insurance plans restores their role as active consumers, making them sensitive to the cost of routine care.

Pro-competition rules: Outlawing contracting clauses that prevent insurers from steering patients to lower-cost, high-quality providers would enable true price competition.

And, yes, the coding system has to be blown up.

These are the pillars for a functioning market. The path to affordable, high-quality healthcare lies in dismantling the broken administrative state that created this crisis and finally allowing the discipline and dynamism of the free market to work.

What employers can do now

Change will not come from legislation. It will come from employers who refuse to keep funding a broken system. So, what can you do right now? More than you think.

Demand real transparency. Not “chargemaster” prices that no one pays. Demand real prices for the care your employees receive. If a hospital won’t tell you what a procedure costs before it’s performed, you shouldn’t contract with them.

Steer to value, not networks. Stop buying broad networks full of high-cost, low-quality providers. Build narrow networks around providers who deliver outcomes at reasonable costs and exclude those who don’t.

Stop negotiating from weakness. You’re one of the largest purchasers of healthcare in your market. Act like it. Reference-based pricing, direct contracts, centers of excellence—these tools exist. Use them.

Make healthcare a C-suite issue. This is no longer an HR benefits problem. It’s a strategic business issue that belongs in the CFO’s portfolio. Manage it like you manage any other major expense.

The path forward won’t be smooth. Incumbent providers will push back, but doing nothing guarantees your costs will keep rising at rates that threaten your business.

It’s time to choose love

No one wants to hear that sixty years of government intervention cannot be fixed with better government intervention. We want to believe that problems have solutions and that experts can engineer better outcomes.

But it’s true, nonetheless.

The only force powerful enough to fix American healthcare is the one we haven’t truly tried: genuine market competition, where prices are transparent, consumers have choices, and providers compete on value.

It’s time to start preparing for your 2026 renewal. So, here is my final LOL:

Lots of luck if you’re waiting for Washington to rescue you. You’ll need more than luck to survive rising premiums, higher deductibles, and costs that climb faster than wages.

Laugh out loud if you must at the absurdity of a system this expensive, this complex, and this administratively bloated. Sometimes disbelief is the only rational response.

But most of all Lots of love.

Because if we truly care about our companies and the future of America, we can’t just laugh and hope. We must act. That means demanding transparency, building competitive networks, and negotiating with strength. Most of all, treat healthcare like the strategic business challenge it is.

Share this with every CFO, HR leader, and business owner who’s tired of being told the next administration will finally fix healthcare. Drop me a line at David.Silverstein@AmazeHealth.com. Your current insurance broker or employee benefit consultant is not likely to steer you in the right direction. Ninety-plus percent of them have fallen victim to earning too much money while doing too little work. It’s time for you to rethink everything.